AKE BUENA VISTA, Fla. -- Until Pat Gillick's election on Monday, since the Baseball Hall of Fame opened for business in 1936, only three men who spent their careers building clubs have been inducted.

Three!

Ed Barrow, who built the first Yankees dynasty in the 1920s.

George Weiss, who built the next Yankees dynasty in the 1940s.

And Branch Rickey, who invented the modern farm system, and then signed Jackie Robinson to smash baseball's color barrier.

That's it. Until Monday, when the greatest GM of our generation and one of the best of all time was elected by the Expansion Era Committee.

And what did this modern genius, this brilliant builder, have to say?

"The job of a GM is not to select players," Gillick said in what must have come as stunning news to the 30 GMs currently gathered here at the horse-trading swap-meet that is baseball's Winter Meetings. "It is to select the correct people to select the correct players.

"I really think the job of a GM is to select good evaluators."

There are many reasons why Gillick has excelled in the game during his half-century of devotion to it, and in particular during his memorable GM stints in Toronto, Baltimore, Seattle and Philadelphia. Two of them are his innate ability to select the correct people across the board -- evaluators and, yes, players -- and his humility.

Gillick, who remains a special assistant to Phillies GM Ruben Amaro, never thought he had all the answers. What Gillick had were all the right questions, followed by some pretty good ideas.

Even at 73, while holding onto his core principles, Gillick remains relevant, easily navigating his way through a game radically different than it was when he first broke in during the early 1960s.

| |

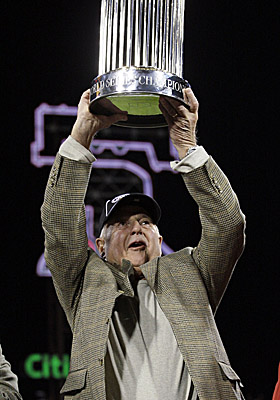

In 2008, as general manager of the Phillies, Pat Gillick hoists the World Series trophy after Philly beat Tampa Bay in five. (AP) |

"I do believe that the core of a club, the nucleus, should be homegrown. They set the tone. Look at the Yankees with Derek Jeter, Jorge Posada, Mariano Rivera and Andy Pettitte. Same thing in Philadelphia with Ryan Howard, Chase Utley, Cole Hamels and Jimmy Rollins. They're the core of the club."

His genius is in his attention to detail. A few years ago, for a piece about the way technology has changed the game, I talked with Gillick about the digital age allowing for trade talks to be conducted via e-mail and text messaging. No, he said, that was one area where he hadn't changed. He still preferred to conduct that part of his business over the telephone or face-to-face in venues like these winter meetings.

Why?

Well, Gillick explained, if he was talking with another GM about a potential trade, maybe there would be something in his rival's voice that would give Gillick a clue. An inflection. A pause. Something that maybe would allow Gillick to read into a snow job, something that would allow him to determine that the opposing club was maybe too eager to give someone away and maybe he should investigate further.

Basically, Gillick was saying, you can learn an awful lot about people by watching. And listening. Things you simply can't pick up when an electronic message dings in your in-box.

The subject came up again Monday when someone asked Gillick about the trend of certain younger GMs to rely more on their computers and quantitative analysis than on watching games themselves.

"I think you have to watch the game, I really do," Gillick said.

Yes, he said, he understood the thinking behind computer reliance, that maybe someone didn't want emotion to interfere with what should be an analytical decision. Heck, Gillick said, he's emotional himself.

"You have to use both," he said of scouts and computers. "Why have statistics if you're not going to use them? But I think as for the caliber of player as you're evaluating ... does he have passion? What's his body language? Seeing how he interacts with other players.

"I think that all goes into the evaluation of a player."

Through more than two decades, nobody this side of maybe John Schuerholz in Atlanta -- the next executive who will go into the Hall of Fame, likely in 2013, when the Expansion Era Committee next votes -- has done it as consistently well as Gillick.

"One thing I think is very important is character," he said. "When I first started out, I used to think it was 70 percent ability and 30 percent character. But the longer I've been in it, I think it's 60 percent character and 40 percent ability."

Gillick was the architect of Toronto's back-to-back World Series championships in 1992-1993, the masterstroke of which came during the 1990 winter meetings when he was part of one of the biggest blockbusters ever, along with then-San Diego GM Joe McIlvaine, acquiring Joe Carter and Roberto Alomar from the Padres for Tony Fernandez and Fred McGriff.

He was the GM the last time the Orioles made the playoffs, in 1997.

In Seattle, in the immediate aftermath of the departures of Ken Griffey Jr. and Alex Rodriguez, Gillick constructed a Mariners team that won 116 games.

And in Philadelphia, he built just the second World Series title team in Phillies' franchise history.

Tellingly, none of these three clubs have been to the playoffs since Gillick left.

Impressively, Gillick won in the AL East with two clubs not named the Yankees and Red Sox. Neither the Blue Jays nor the Orioles have been much since.

Gillick has a knack for easily moving into a situation and working with those around him. He has not been an executive who immediately "blows things up" in a new situation and brings in his own people.

In his last three stops, he never even fired the manager he inherited. In Baltimore, he kept Davey Johnson, who had been hired by owner Peter Angelos just before him. In Seattle, he and Lou Piniella formed a dynamic duo. And in Philadelphia, he kept Charlie Manuel -- who went on to win a World Series for him.

"I think I've only known five or six people he's let go," says Gordon Lakey, the Phillies' director of scouting, and also one of Gillick's top aides in Toronto.

Lakey always has admired how Gillick, in meetings, will seek everyone else's opinion first, soaking in all of the information he can, before he expresses his own thoughts.

"He's one of the few people you can say makes everyone around him better," Lakey says.

Lakey also tells a terrific story, which he related to Tyler Kepner of the New York Times the other day. At a tryout camp in Mississippi some 40 years ago, Gillick was perplexed by something about one of the players. It wasn't until after the workout, when he was in the car with the area scout, that it finally came to Gillick.

"That kid changed his name," Gillick said. "That kid's been around. His last name was Pettigrew before."

It's all in the details. Always has been for Gillick, one of a kind, a true, slam-dunk Hall of Famer.

extracted from cbssports.com

5:54 a.m.

5:54 a.m.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario